|

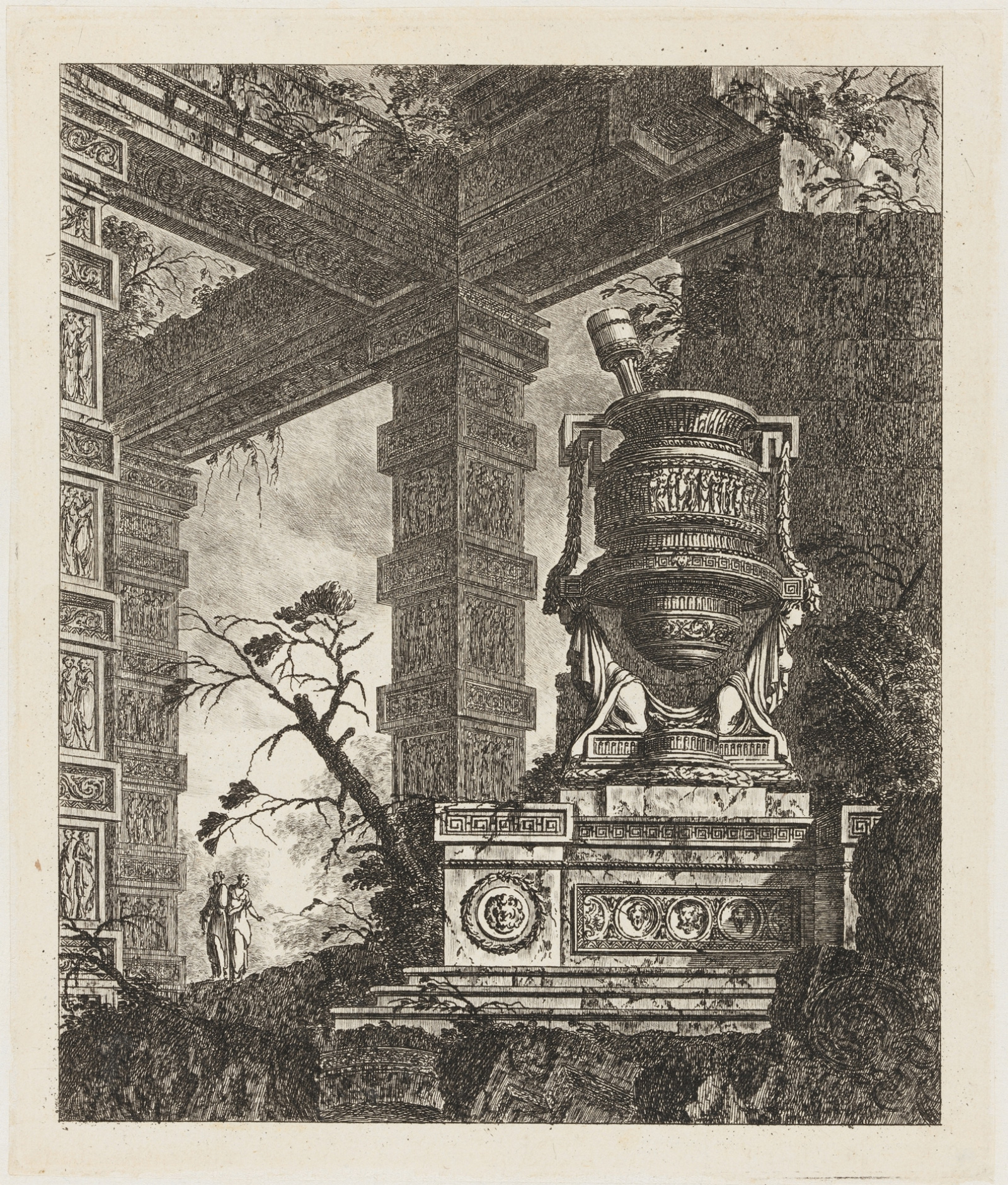

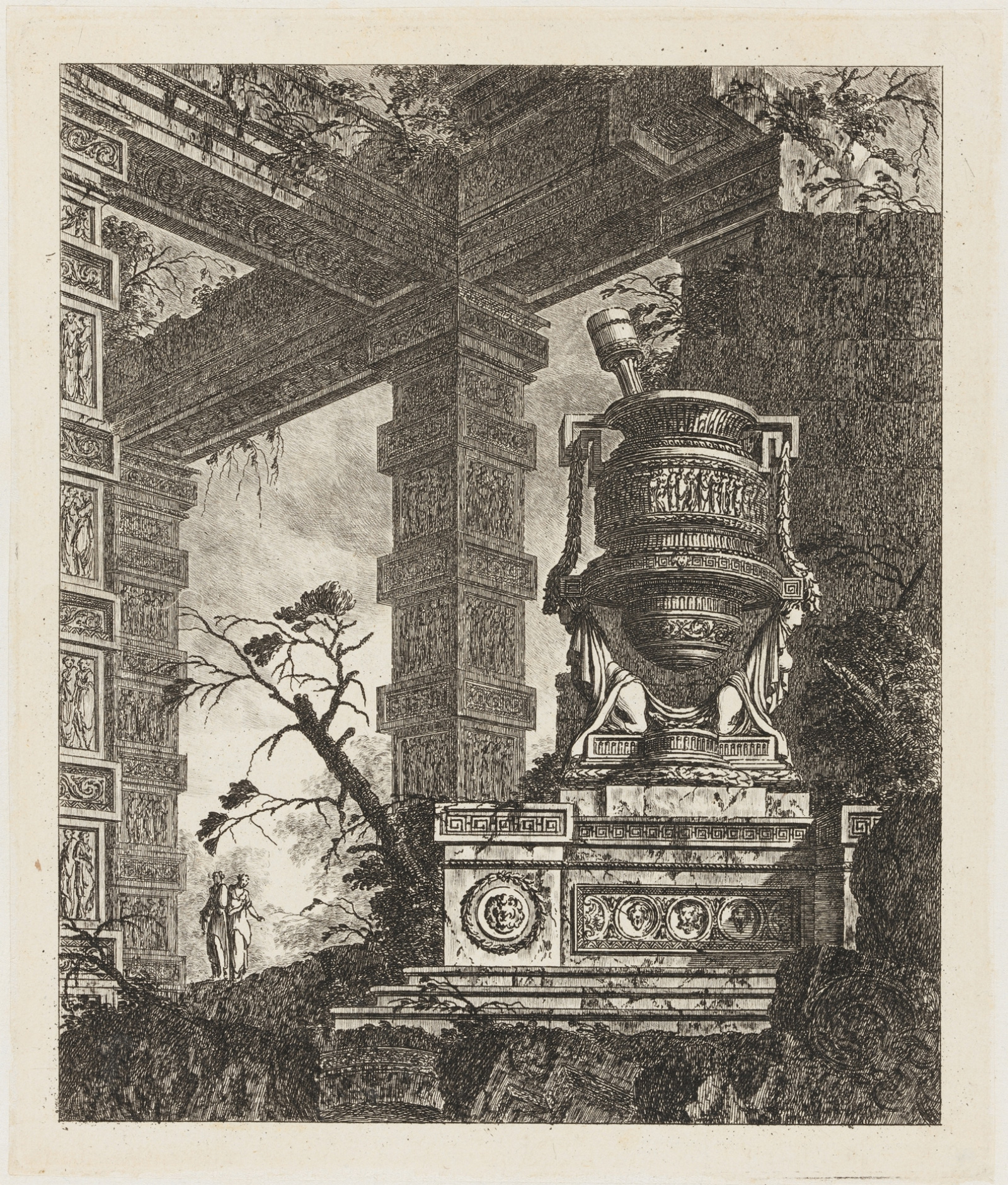

| Monster vase by Jean-Laurent Legeay. |

The two-handled vase has an intrinsic appeal for artists. The form is elegant and it may suggest the human form. Artists since the Renaissance have been fascinated by it and the way it can present itself for ornamentation. Enlarged and placed on a plinth, it becomes a sculpture, like this vase (

below) of unknown provenance in Floral Street, London. Adding two handles to a vessel defines a front and back that's useful in decoration.

|

| Floral Street, London |

There was a mania for vases in late 18th century Europe - vases used in interior decoration, vases for gardens, vases as building motifs, and ultimately vases as grave ornaments. They didn't contain anything, they were simply to be looked at or to communicate the taste of the owner. If a vase was useful it was not as a vase but as something else wittily got up as a vase - a knife box or a stove. Josiah Wedgwood said that "an epidemical madness reigns for Vases, which must be gratified." With characteristic talent and energy he gratified it, making clever and beautiful adaptations of Classical models. Vase Mania drove him to technical innovations in ceramics. In order to meet the demand, he changed his method of production and marketed his products with vigour. With some justification he titled himself "Vase Maker General to the Universe".

The excavations at Herculaneum and Pompeii had produced masses of material for architects and designers and they helped to create the Neo-Classical style. Archaeology uncovers more vases than sculptures, so vases became emblematic of the ancient world and were studied in depth. The finds of southern Italy (loosely called "Etruscan") were disseminated through books of engravings. Architects and designers looked for models in Anne Claude de Caylus's

Recueil d'antiquités égyptiennes, étrusques, grècques, romaines et gauloises (1752-1755) and

Giovanni Battista Piranesi's

Vasi, candelabri, cippi, sarcophagi, tripodi, lucerne ed ornamenti antichi (1778) (

below).

|

| Giovanni Battista Piranesi's Vasi, 1778 |

Sir William Hamilton, British ambassador to Naples, amassed a large collection of vases, which he donated to the British Museum. His

Collection of Etruscan Greek and Roman Antiquities (1767) was intended to influence taste. "We think also, that we make an agreeable present to our manufacturers of earthenware and china and to those who make vases in silver, copper, glass, marble, etc.," he wrote. "[T]hey would be glad to find here more than two hundred forms, the greatest part of which are absolutely new to them; there, as in a plentiful stream, they may draw ideas which their ability and taste will know how to improve to their advantage, and to that of the public."

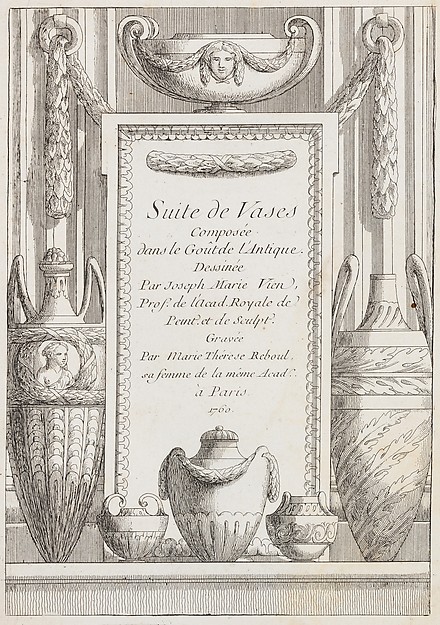

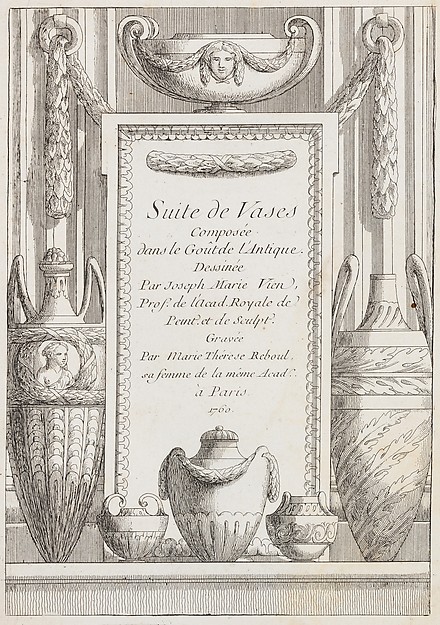

There were other vase collections by J.F.J. Saly (1746), J. M. Vien (1760) (

below), C.de Wailly (1760) and E.A.Petitot (1764)

|

| Suite de Vases, Joseph Marie le Ven (1760) |

Wedgwood owned Hamilton's

Collection and was himself a collector of vases, to the despair of his wife. She wrote, "I am almost afraid he will lay out the price of his estate in vases he makes nothing of giving 5 or 6 guineas for." Well abreast of the antique taste, Wedgwood called his new Stoke-on-Trent factory "Etruria". It gave its name to the surrounding district and anyone like me who has spent any time in Stoke-on-Trent thinks of Etruria as a dirty industrial area in North Staffordshire, not as a place in Italy.

|

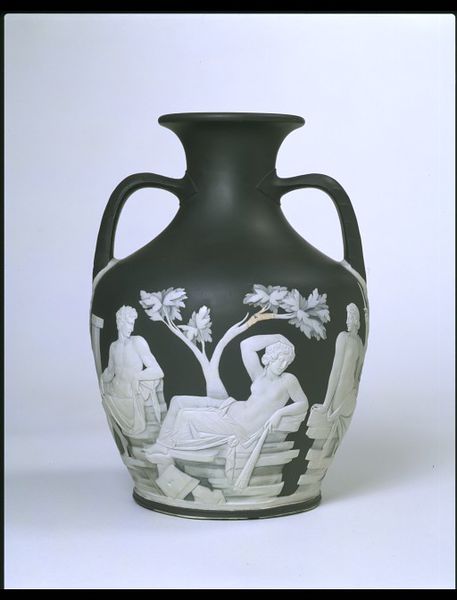

| Wedgwood Black Jasper Vase |

|

| Wedgwood Agate Vase |

|

| Wedgwood Porphyry Vase |

|

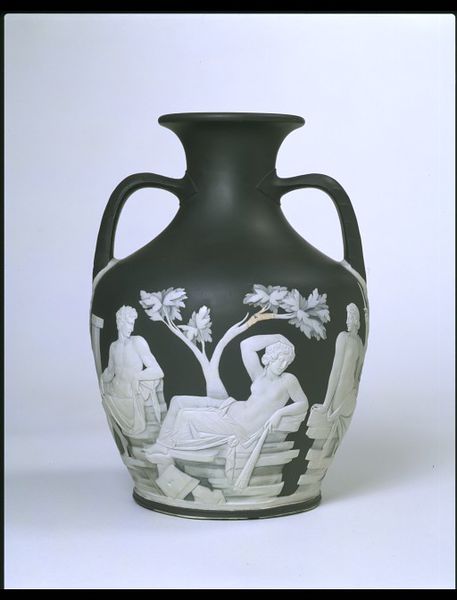

| Wedgwood Portland Vase |

Wedgwood rapidly capitalised on the taste for vases. Here are representative vases from his output in different ceramic media: a vase in black Jasper ware, an agate vase in which clays of different colours are mixed, an earthenware vase with a so-called porphyry glaze, and the famous Portland vase, also in Jasper ware. Wedgwood developed the Jasper body specifically for imitations of antique vases, taking many years and encountering many problems. It's a vitreous body that doesn't need a glaze. He worked to high standards and had difficulty in finding the right craftsmen. (He's famous for going round the factory and knocking down anything that wasn't good enough for him.) He had to find ways to make unique designs pay. "It is this

time losing with

Uniqueness," he complained, "which keeps ingenious Artists who are connected with men of great taste poor." He had to improve productivity, driving down the piece rate he paid, but doing his best to persuade his workers that his methods would increase their wages in the long run because they would be making more.

Wedgwood was observed by Matthew Boulton to be "scheming to be sent for by his Majesty." He marketed his vases to aristocracy and royalty, charging the highest prices possible. At the height of Vase Mania, vast sums were paid for desirable items. In one auction, a tea kettle was sold for 130 guineas.

Decorative vases in the antique style were made by Wedgwood's rivals in Staffordshire, the factories of Derby, Worcester, Coalport and at Sèvres. Nor was pottery the only medium. Matthew Boulton, the Birmingham metalworker, made teapots, hot-water urns, egg caddies and chandeliers in vase forms. Silver vases were used as ornaments and given as prizes. Wooden knife boxes were made to look like vases and Robert Adam designed a cast iron stove to look like a vase. During Vase Mania and after, the vase motif proliferated in surface design, in marquetry and on textiles.

|

| Silver vase given as a prize |

|

| Wooden knife box |

|

| Robert Adam Stove |

Vase Mania peaked around 1772. Wedgwood saw the way the wind was blowing and decided to make more and to sell more cheaply. "The Great People have had these Vases in their Palaces long enough for them to be seen and admired to the

Middling People," he said, "which Class we know are vastly, I had almost said, infinitely superior, in numbers to the great, and although a

great price was, I believe, at first necessary to make these vases esteemed

Ornaments for Palaces, that reason no longer exists, and the middling people would probably buy quantities of them at a reduced price."

Some artists faithfully copied antique vases in their engravings, others invented fantasy vases that never were and never could be. The vase had become separated from function, turned into a marker of taste, an object of contemplation and a stimulus to historical reflection or emotion. In Jean-Laurent Legeay's

Collection de divers sujets des Vases, Tombeaux, Ruines et Fontaines (c. 1770), the antique vase becomes Romantic and mysterious, recalling Piranesi's

imaginary prisons. In

Legeay's drawing at the top of this post, a huge vase and pestle stands in a ruined landscape dwarfing the human figures. The image uncannily anticipates the appearance of a neglected Victorian cemetery, in which the tomb-vase has been routinised. (I've written more about the Victorian funerary urn

here.) Ennemond-Alexandre Petitot in a different kind of fantasy humanised the vase form (or vasified the human form) in this drawing of

The Greek Bride (

below).

|

| Ennemond-Alexandre Petitot, The Greek Bride |

From stove vases, vase brides and enormous vases in a landscape it's a short step to vases on funerary monuments. Urns appeared on tombs ten years after Vase Mania had passed its peak. In the Victoria and Albert Museum, there is a monument by Joseph Nollekens, erected 1786 but designed earlier (

below), with a fine draped urn, which the V&A describes as "a standard classical symbol of death". Next to it is a monument in Coade stone to Sir William Hillman (1800), with a vase on a pedestal attended by a mourning woman - a motif that might have been taken from Legeay.

The funerary urn was clearly from the vocabulary of Neo-Classicism, a remnant of Vase Mania, and although symbol hunters

speculate endlessly about its meaning, there's no evidence that it means anything except an association with the antique and the bestowal of honour.

|

| Design for a monument by Joseph Nollekens, erected 1786 |

Stefanie Walker (ed.) Vasemania - Form and Ornament in Neoclassical Europe, New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004.

Jenny Uglow, "Vase Mania", in Maxine Berg, Elizabeth Eger (eds.) Luxury in the Eighteenth Century, Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2001.

No comments :

Post a Comment